Our son William was born at full-term in early 2018, affected by Treacher Collins Syndrome (TCS). TCS is a rare, genetic condition affecting development – particularly the way the cheekbones, jaws, ears and eyelids are formed. TCS can cause problems with breathing, eating, hearing and speech. There is a spectrum for TCS and therefore its impact varies between people with the condition.

We knew there was a 50/50 chance William could have TCS because of family history, but our scans were indicating that there was no sign of the more severe characteristics so I had enjoyed a pretty straightforward pregnancy, excited at the prospect of expanding our family.

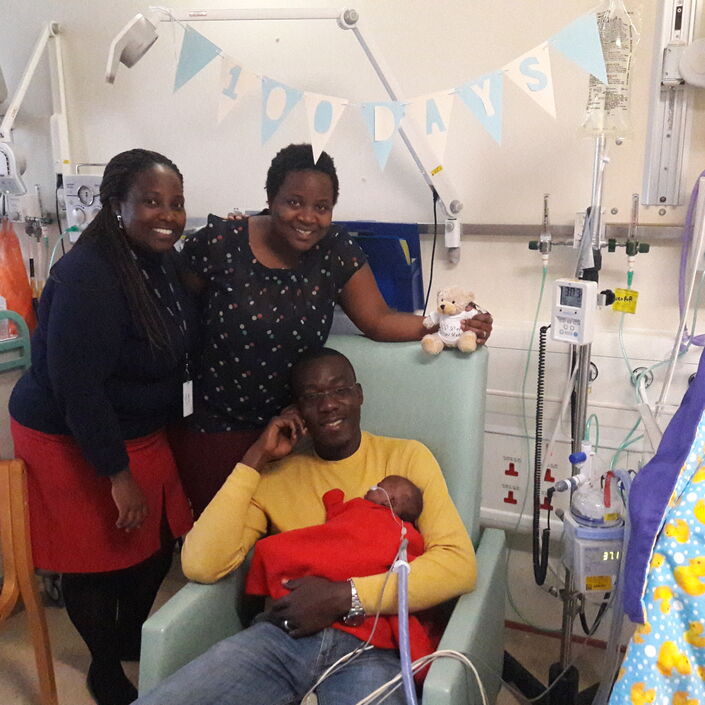

Being mindful of the potential for TCS, I opted for a c-section to ensure that William’s arrival was calm, controlled, and that there would be paediatricians present should there be an issue with his airway. It was a completely life changing moment when he came out as it was clear straightaway that he had a severe version of TCS. He cried loudly, but it was immediately obvious that once he relaxed his small jaw compromised his breathing. So he was wrapped up, thrust in front of my face for what felt like a second, and then was whisked away to NICU.

Paralysed by the epidural from the c-section, I was stitched up and left in the recovery room before being moved to the ward while my husband went to NICU to be with William. He kept coming back to keep me updated, but it was all too much to take in. I think the staff and I were all in shock. I certainly was; I couldn’t stop shaking.